One of the opportunities that is coming for Structural Integrators and other ‘afascianados’ lies in the area of scar remediation. This opportunity lies both in private practice, where C-section, post-partum or endometriosis scars are all too common. Scarring from bone breaks or tendon ruptures or contusions – all these follow the same set of rules of repair (though conditions differ, in individuals). The fascial restrictions within and between muscles are working with the same process. Even though we don’t call it ’scarring’, it’s the same physiology of ‘remodeling’, with the same result in restricting movement.

Outsider of private practice, the possibilities within the medical system are also broad. Not to take away from all the scar protocols in physiotherapy, but fascia-savvy practitioners can add to the work of softening and revivifying scarred areas beyond what is taught is regular physiotherapy school. Here are three tips for working with scar tissue:

1) Change the ‘gel’ as well as the fiber

Scars involve extra fiber, but there are also alterations to the ground substance. Depending on the genetics, normally porous gels like hyaluronan become infused with chondroitin, keratin, or keloids that make the scar rubbery. If the scar is welted or raised, check whether it feels gelled up in the general area. then loosening the ‘rubber’ is the first line of defense. Very specific stretching can help re-hydrate these proteins, but the genetic differences mentioned may limit how much this part of the scar can change – but it is definitely worth a try.

2) Combing out the tangle

Scar tissue is somewhat pulled into a line, which lines up fibers along the line of the scar, and binds them tightly together. Around and through the scar, the fibers arrange themselves like felt, omnidirecitonal and woven every which way. As when my little daughter’s hair got tangled, the ’no tears’ way of getting those snarls out is the find the edge of the tangle, and comb or brush it out a little at a time. Definite, specific touch, combing out the scar and surroundings. Don’t go for the center of it all immediately. Ease your way in a little at a time – and persevere – it does dissolve with patience. Some scars are so old or so large that they cannot be completely erased, but most can be ameliorated.

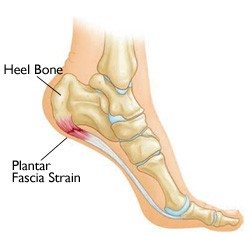

3) Detaching the scar

The following is my ‘practice-based evidence’ – anecdata – but boy, howdie, does it work for me. Every deep scar (deeper than the fascia profundis) seems in the end to anchor itself to to a nearby bone, or more precisely to the periosteum (outer fascial coating). I have felt (in practice) and seen (in dissection) these thin fascial bands that reach out from the scar like the large latitude lines in a spider web that attach it to the rest of the world. I have even found these lines extending several inches from tiny laparoscopic scars to the costal arch or ASIS.

Dissolving these little strings has been shown to be the most effective in keeping the scar from re-establishing itself. So as you come to scar, ask: to what part of the skeleton is this scar attached? C-section scars are often linked to the nearby public bone, such that in addition to easing the gel and combing the fiber, I am looking for the thin thread that goes from one end of the scar (usually the bit sewn last if it’s surgical) to the nearby pubic tubercle. Finding and stretching this string, and most importantly, pressing into the precise spot where the periosteum and the scar meet, dissolving and separating the two.

The ’scar tail’ is the closest I have to a ‘magic trick’ on scars. So much of the limitation of ’scarring’ is in the mind – people stop moving the place that’s been hurt – but when you are down to the scars in the fascia, I hope this helpful.

— Tom Myers

Abstract: Every year, surgical interventions, traumatic wounds, and burn injuries lead to over

80 million scars. These scars often lead to compromised skin function and can result in devastating

disfigurement, permanent functional loss, psychosocial problems, and growth retardation. Today, a

wide variety of nonsurgical scar management options exist, with only few of them being substantiated

by evidence. The working mechanisms of physical anti-scarring modalities remained unclear for

many years. Recent evidence underpinned the important role of mechanical forces in scar remodeling,

especially the balance between matrix stiffness and cytoskeleton pre-stress. This perspective article

aims to translate research findings at the cellular and molecular levels into working mechanisms of

physical anti-scarring interventions. Mechanomodulation of scars applied with the right amplitude,

frequency, and duration induces ECM remodeling and restores the ‘tensile’ homeostasis. Depending

on the scar characteristics, specific (combinations of) non-invasive physical scar treatments are

possible. Future studies should be aimed at investigating the dose-dependent effects of physical scar

management to define proper guidelines for these interventions.To read the paper, click here: ebj-03-00021-v2