Note: Tom Myers refers to this article from Scientific American.

This article in Scientific American prompts three responses, two of them predictable, but afascianados, stick around for the third.

First is the amazed gratitude of living in an age when we can witness such power in the scientific ‘religion’ that it can perform such miracles.

The second reaction is that this is just one more brick in the wall of seeing ourselves as machines with replaceable parts. We are machines, as evidenced here, but we’re so much more than that that I hate the constant reference to our body as merely a mechanical device for carrying a mind around.

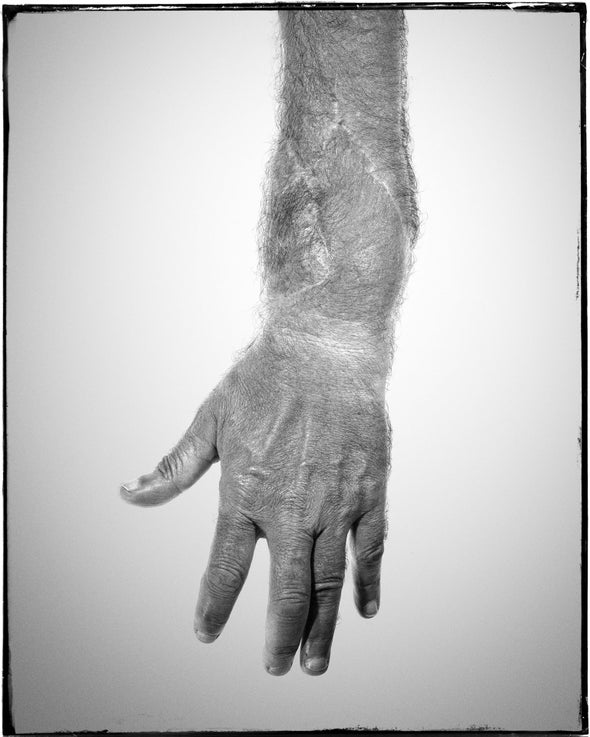

(Second-and-a-half reaction is to wonder whether a hand transplant conveys memories in the way that heart transplants have been known to do. If these hands could only talk!)

The article focuses quite properly on the ‘upstream’ recovery in the spinal cord and brain – right in there with the bio-psycho-social model of pain: a bio-psycho-social model of trauma recovery.

But my third point is made right in the beginning of the article, describing the process in 1964, but it is much the same today.

In this surgery:

“The team stitched together the delicate, tubelike fascicles, nerve-surrounding sheaths that they hoped would guide sprouting sensory and motor nerves.”

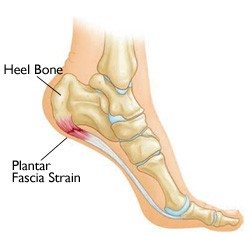

Nerve axons – have you watched one of our dissection livestreams? – are as soft and insubstantial as pudding. No way you can ’sew’ a nerve itself. So notice they sew the fascial sheath around the nerve – that they can, albeit with microsurgery, sew one end of sleeve to another.

Approximately 65% (it varies) of any given nerve is actually fascia. Axons stretch easily, but they do not take kindly to shear – that’s what happens in a concussion: the shock wave shears axons. The progressive fascial coatings around the axons – roughly equivalent to the rubber part of an electrical wire – are what they can sew together.

Only if they are sewn together can the nerves find their brothers and sisters on the other side of the break – in this case the gap to the nerves in another, foreign arm. If the gap is too large, the nerve cannot regrow. If the sewing stitches have a glitch in them, the nerve may grow awry or not be able to bridge the gap at all.

You want to know a real miracle? The docs perform a miracle enough to get the little nerves and sew their outer tunics together. But each of those nerves might contain a hundred to a thousand actual neurons, and they each need to hook up with a specific neuron at the other side – and in this case, with a nerve it’s never even ‘met’ before.

So how do all the individual nerves link up with the individual nerves in the donor arm? You may well ask. It is done by some kind of chemical signature obviously, and requires, as the article says, immune suppression. But to my mind, as miraculous as this whole thing is, the ability of nerves to hook up with their counterpart if placed in proximity is gob-smacking.

— Tom Myers, Clark’s Cove, Maine