Thanks to Anatomy Trains teacher Lauri Nemetz for putting together this post. Pictures, unless noted, courtesy Lauri Nemetz.

When grapes turn

to wine, they long for our ability to change.

When stars wheel

around the North Pole,

they are longing for our growing consciousness.

Wine got drunk with us,

not the other way.

The body developed out of us, not we from it.

We are bees,

and our body is a honeycomb.

We made

the body, cell by cell we made it.

~Rumi (translated by Robert Bly)

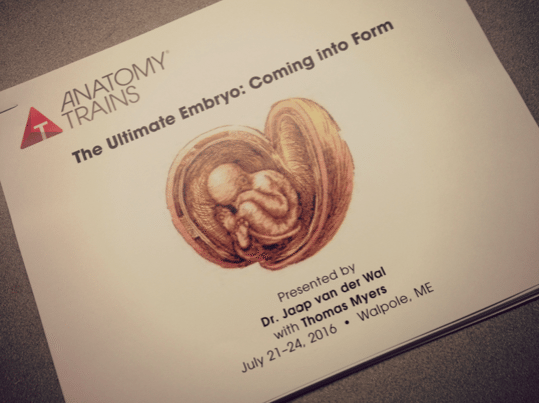

Jaap van der Wal presented as part of the Anatomy Trains 2016 summer series through story, movement and imagery. He has rich background as an MD, PhD, anthroposophical morphologist (say that quickly) and has taught extensively as an anatomy teacher and is known for his work in embryonic development as well as the concept of dynaments (muscle and connective tissue working in tandem for joint stability- for more reading look to Tom’s article here). For many of us who attended the 4th Fascia Research Congress this past fall in Washington D.C., he captivated the audience with his weavings of anatomy and story in a thoughtful narrative that combined spirit and matter, leaving many of us wanting more. Equally able to waltz in the academic and esoteric worlds, he is an intriguing figure and has developed his work to look at the gesture of form in the human body and in nature as a whole. His recent four-day intensive to a packed room of forty in the Anatomy Trains classroom in Maine was equally impressive.

In this course he explored spiritual embryology and phenomenology, while taking us through the shifting anatomical dance of the embryo as it develops. He also gave each of us the importance of our own unique journeys, stating, “you cannot reproduce a biography,” emphasizing the unique interaction each life has in the world that is never repeatable.

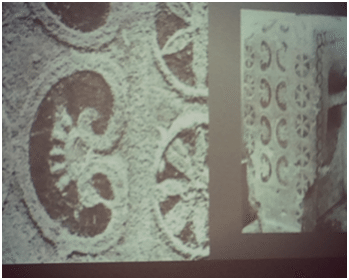

Jaap truly dances as he describes the folding and unfolding gestures during the process of human embryonic function. He pulls from several inspirations, including the work of Rudolf Steiner, Rumi, Andrew Still, and art from Michelangelo, Da Vinci, Greek art and more. Citing the theories of Blechschmidt, he comments on the fact that movement is pre-exercised in the body and that motion is the primary force, while form is secondary. As he stated, “you are a process and you are constantly shaping your body.”

In reflecting on dissection lab, he commented on his time teaching in gross anatomy, remarking that his medical students always wanted to know about the “who” in the bodies they worked with, and that this question of “where am I?” is relevant to us as humans and in our development. Our perception, another area of great interest to Jaap (who often refers to himself by his first name, in third person), is a uniquely human trait. He remarked that we perceive the coldness of a deceased body, or the heaviness of a sleeping child in a very different way that a thermometer or scale could ever measure.

Van der Wal would occasionally talk about his academic days and his ability to teach mainstream anatomy with a wink and “see I know my names” but clearly his work has always been swimming between worlds. He joked that the morphology crowds would be equally stunned by his work in anatomy, while his university faculty colleagues would wonder at his esoteric leanings. With his doctoral thesis, presented at the University Maastricht in 1988, “The Architecture of the Connective Tissue in the Musculoskeletal System—An Often Overlooked Functional Parameter as to Proprioception in Locomotor Apparatus”, Jaap explored his early ideas of not only tissues in parallel, but his early interest in embryology. As noted in the article:

“The primary connective tissue of the body is the embryonic mesoderm. The mesoderm represents the matrix and environment within which the organs and structures of the body have been differentiated and therefore are embedded.”

Tom, enjoying the course like the rest of us, did allow moments to throw in questions and opinions. What truly guides development? Where is spirit? Is the current model of the nervous system incorrect? There is an enormous respect between these two great minds and thinkers, and I thoroughly appreciated the ability to disagree and dialogue as well as their shared loved for the human body on many levels.

Throughout the entire course, Jaap noted that the heart, so prominent in early embryology, is about rhythm and that rhythm is time and space. In a sense, the beating heart is constantly dying and recreating in form. As noted in his chapter, The Incarnating Embryo—The Embryo in Us (2015 in Holistic Palpation, Morphodynamic and Biodynamic Principles in Health and Disease):

“…with the heart a primordial ‘Here’ is developed in the embryonic organism. Very soon after the establishment of the primitive blood vessel loop (not before the fourth week there will be a closed circulation) the heart starts to beat at about the 21st day after conception.” He also showed us through a series of photos and illustrations that the heart begins more gestures of gastrulation (folding inwards) during this critical time of development.

From the fifth/sixth week onwards, we start the gesture of unfolding, to lead to our eventual up-rightedness. One of the most interesting mind shifts for me was in thinking of the development of our embryos vs. other animals. He started this dialogue with the Goethe quote, “The animal gives in where man keeps standing.” He cited Louis Bolk, the Dutch anatomist who lived in the early 1900s and studied prematuration in humans. Whereas Desmond Morris would popularize the theory of the “naked ape”, Bolk noticed in dissecting chimpanzees in lab that the foetus starts out naked like us, except for hair on its head. Actually, rather than remarking how closely apes and chimpanzees look like us, we perhaps should be commenting how closely we resemble these other creatures.

Where we split is an interesting anatomical oddity for humans. All creatures start with remarkably similar features, but then begin to specialize quite early and quite specifically. Animals are born ready to walk, run, etc. within hours, sometimes minutes of their birth, while we take time to develop. Bipedalism is not the same as up-rightedness, and Jaap equates growing upright as a gesture of the soul. Unlike other creatures, our center of gravity when we are bipedal retains an organization inside the body cavity. Because we retain our embryonic self, we are bodily poor (in terms of specialization), but mentally rich.

In this last picture of the group (taken by his wife) he asked us to make a gesture. Jaap sees the embryo (and us) as a continuous action in process. Both dying and birth are gestures of development. Going back to the Rumi quote that Jaap often referred to throughout the workshop, it may well be that we are not simply a body shaping what and who we become, but rather a connected being shaping into form.