Perhaps you’ve seen this story about CNN correspondent Miles O’Brien needing an amputation:

http://www.cnn.com/2014/02/25/health/miles-obrien-amputation

Nowadays it’s getting better, but a lot of docs – if they had heard of fascia at all – knew about it in the context of the procedure called a ‘fasciotomy’. Just as a tracheotomy is cutting open the trachea, a fasciotomy is cutting open the fascia. But why cut the fascia?

Blood vessels and nerves travel down through your limbs in neurovascular bundles surrounded by a fascial sleeve. You can feel such a bundle by putting one thumb well up into the other armpit and pushing out toward the inner surface of the upper arm bone (medial humerus). Run your thumbpad back and forth to feel the nerve twang; you can follow this up toward your brachial plexus or down toward your ‘funny bone’.

These bundled but vulnerable ‘viscera’ snake around your limb bones, muscles, and joints in very clever way. In an award-winning design by God, your Mom, or Darwin (pick your religion), they hide from direct pressure and outside insult, so that even with all the crazy things we do with our limbs, we rarely impinge on their vital job of bringing blood and signals to and from the hands and feet. True, you can sleep on your arm and wake up with pins and needles, or bang your funny bone (ulnar nerve, really) if you hit the edge of a chair just right, but neither of these minor annoyances last long enough to require a fasciotomy.

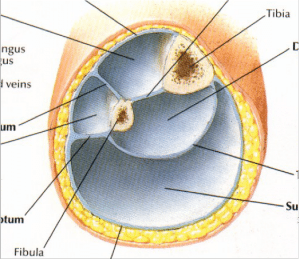

Fascial compartments of the lower leg

Fascial compartments of the lower leg

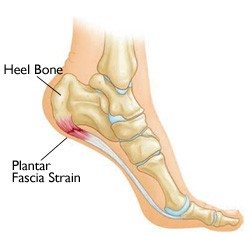

This poor fellow Miles had a very unfortunate and precise injury that created swelling sustained enough to put so much pressure on the blood vessels that it cut off the circulation to his arm and he lost it, poor man. Most of the cases requiring a fasciotomy, however, are in the legs of athletes, where muscle development gets so strong and their fascia doesn’t expand to meet muscle development. In these cases the pressure builds within these compartments (hence ‘compartment syndrome’, used to be ’shin splints’) until it pushes on these neruovascular bundles and cuts off circulation – which is at first annoying, but can get dangerous.

In these cases, fasciotomy is a surgical solution, and is often performed out near the intermuscular septa of the lateral compartment, as well-illustrated here:

If this seems a little drastic to you, I have to agree. It can be successful in some cases, but in others it either doesn’t work, or works only temporarily because either 1) the person continues to play hard and still doesn’t have ‘expansive’ fascia (too little elastin? Too much cross-bridging? I don’t know), or 2) the scar tissue caused by the surgery contributes, some months post-op, to the inability of the fascia to accommodate the growth of the muscles. Admittedly, I get the failures coming through my door more often than the successes, so my view is a little skewed.

What you can do as a manipulator or with a myofascial roller or balls after surgery is a good deal less than you can do before, because of the scar tissue’s reduced response to stretching and opening. Worth a try, though, anyway. But if they come to you first, before it gets too bad, you can sometimes / often relieve the symptoms temporarily (meaning they need to see you every so often, depending on their pain and activity level) or you can sort it out for good.

You want to start out going longitudinally to open the two intermuscular septa along either side of the peroneals / fibularii (see diagram from Netter above), and then open the transverse posterior septum (maybe using our ‘pinch’ technique – see the Deep Front Line Part 1 DVD). Working on soleus and gastroc will do little for them, we need to open those small compartments deep in the leg from as top to bottom as we can reach.