Every therapeutic situation is unique – culturally and psychologically – such that the best therapist is able to morph him or herself to match a variety of client needs and presentations. Therapists who, for reasons of capacity or personal choice, do not modify their mien to meet the client are subject to the tendency to limit their client base to those who naturally fit with the their style. This limits your effectiveness in your community, and impoverishes the diversity of experience in your practice.

Every therapeutic situation is unique – culturally and psychologically – such that the best therapist is able to morph him or herself to match a variety of client needs and presentations. Therapists who, for reasons of capacity or personal choice, do not modify their mien to meet the client are subject to the tendency to limit their client base to those who naturally fit with the their style. This limits your effectiveness in your community, and impoverishes the diversity of experience in your practice.

Though there are probably other aspects I am unaware of, or forget right now, I modify

my speaking voice in terms of volume, pitch, rhythm, and tone,

my body posture (e.g. dominant vs submissive),

my language in terms of visual, auditory, or kinesthetic imagery,

the space I keep between me and the client,

my mode of taking a history,

what I allow them to do in my office,

and of course the manner of my approach and touch.

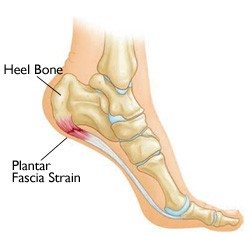

For the past several days, I have been a guest and resident therapist in the house of a great artist and difficult man. I have been working with him – he was recently subject to a debilitating injury – as well as his wife, and his gardner / handyman.

Not unlike other artists we know, this man is right next to impossible – contentious, brilliant, isolated, self-obsessed, and the restriction of movement imposed by an operation on each shoulder has not improved his mood. To approach such a being with nonchalance or any avoidance behaviour will be immediately sensed and (there’s no other word for it) pounced upon. Matching his intensity without falling over into arrogance or confrontation is akin to staying on a surfboard, requiring anticipatory reflexes.

Afterward, I was careful in eliciting his response to the intervention, using my questions to indirectly focus his attention where I wanted it to go. It’s always better if the ‘good idea’ is apparently the client’s.

His companion, equally sensitive but shy, retiring, and inwardly focused, required the tone with which you coax the cat out from under the bed. While her husband required strong stimulation to perceive change, with her a little goes a long way, so I sought to stay under her stimulatory threshold, using primarily cranial and visceral motility work, proffered with a soft voice and hand.

Afterward, I never mentioned the session again, waiting for her to come to me, which, in fact, she did not – but with this type of person there is no value in digging up the seed to see if it has started growing yet; it is best left in darkness.

The handyman, working class and a member of an oppressed minority whose native language was not English, required yet a different approach with a lot of eye contact, little direct touch, a lot of explanation and self-help exercises.

Afterward, I engaged him every time I saw him – “Done those exercises yet?” and letting him ask as many questions as he needed, joshing and teasing him into compliance.

Each of these relationships would have developed if I had been resident, so that the initial approach is modified with the development of trust and familiarity to deepen the bond.

Beware of any client you dismiss, “Oh, he just doesn’t want to change…”, it may be your approach that needs modification. If shifting your demeanour feels like being unfaithful to yourself, I would gently remind you that your precious self is a construct anchored in culture and familial values, and could probably use a little shaking up. In my opinion, expanding your repertoire of approaches is one of the best opportunities for expansion offered to therapists.

-Tom Myers