The upright human posture and plantigrade gait requires a delicate balance to keep the ventral cavity operating at its functional best. Solving problems in the abdominopelvic region has focused primarily on the horizontal belt surrounding it: the transversus abdominis and its fascial connections to the thoracolumbar fascia and neural connections to the levator ani of the pelvic floor.

The upright human posture and plantigrade gait requires a delicate balance to keep the ventral cavity operating at its functional best. Solving problems in the abdominopelvic region has focused primarily on the horizontal belt surrounding it: the transversus abdominis and its fascial connections to the thoracolumbar fascia and neural connections to the levator ani of the pelvic floor.

The concept of ‘core support’ has ramifications to proper sacroiliac stability, lumbar support, pelvic floor health and continence. and a good foundation for respiration – and even on up to shoulder balance and neck strain.

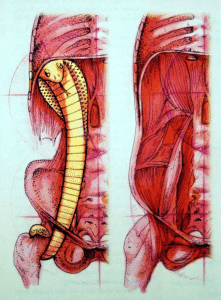

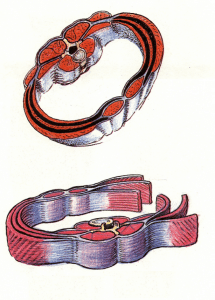

While support in this outer belt is important, and the exploration has produced positive results for patients, less emphasis has been placed on a primary myofascial relationship which is of equal importance to human function, which could be termed our inner ‘cobra’. The cobra lurks inside the belt, and is essential for easy lumbar support of the rib cage, and links the rhythm of breathing and walking.

Our inner cobra is made up of the psoas major muscle and the diaphragm considered together as a functional unit. While these are often depicted as separate in the anatomy books, in the dissection lab the fascial connections are very clear between the diaphragm and the psoas major.

Our inner cobra is made up of the psoas major muscle and the diaphragm considered together as a functional unit. While these are often depicted as separate in the anatomy books, in the dissection lab the fascial connections are very clear between the diaphragm and the psoas major.

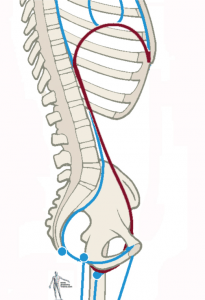

The posterior diaphragm is rooted into three structures: 1) the crura, which blend from the aortic arch into the anterior longtudinal ligament along the front of the lumbar vertebrae, 2) the psoas major (and, if present, the minor) which reaches down from each diaphragmatic dome to the lesser trochanter of the femur, and 3) the quadratus lumborum rooted down to the iliac crest and iliolumbar ligament (and in fascial terms beyond into the iliacus and iliac fascia).

There are two cobras, one on either side of the spine. The tail of the cobra is the lower end of the psoas, curled around the neck of the femur parallel to the pubofemoral ligament. The cobra’s ‘body’ goes forward of the hip joint itself, and then retroperitoneally back behind the organs to lie of either side of the lumbar spine. The ‘hood’ of the cobra is the spreading dome on each side of the diaphragm. In the image, the cobra’s face would be at the front of these domes, approximately at the end of the 6th and 7th ribs.

Considered as a functional whole, the balance of these two muscles is essential for respiratory and spinal health. Get the balance and function of these two cobras correctly, and it will matter less whether your patient has ‘washboard’ abs or ‘washtub’ abs. With a strong and balanced cobra, tight abs are less necessary to upper body support.

Considered as a functional whole, the balance of these two muscles is essential for respiratory and spinal health. Get the balance and function of these two cobras correctly, and it will matter less whether your patient has ‘washboard’ abs or ‘washtub’ abs. With a strong and balanced cobra, tight abs are less necessary to upper body support.

When the cobra gets too short, the cobra lifts up and exposes its throat, so to speak – in postural terms, the lumbars get more lordosis and the rib cage tilts back, restricting breathing in the back of the diaphragm. When the cobra loses tone, the head of the cobra dips, the lumbars fall back and the rib cage falls, restricting breath in the anterior part of the diaphragmatic domes.

Learning to read and correct the position of the cobra offers a new aspect to core support that supports the upper body easily, dynamically, and with less residual tension than just slamming down those abs.

Endlessly tightening the TvA, though it does offer increased support, also restricts movement, especially respiration and the organ excursion from respiration essential to their health. Your organs are ‘massaged’ neatly 20,000 times per day by the breath – restriction of the ‘abdominal belt’ and the ‘abdominal balloon’ may create support at the cost of essential function.

Learning to see, assess, and treat the ‘cobra’ of the psoas-diaphragm complex renders core support truly at the core, linking pelvic neutral and lumbar neutral with an easily functioning diaphragm.

-Tom Myers